How can we do better? How can we redirect a process that we have shaped to be destructive to the natural world into one that is regenerative?

BUILDING AS CLIMATE ACTION

February 02, 2022

Climate action comes in many forms. From individual habits to federal policy, corporate initiatives to art installations, climate action is often perceived as something other than business as usual. Making a better consumer choice is an extra effort, or a “green job” is something outside the norm. The reality is, we need to readjust every aspect of our lives – and quickly – to reach the necessary targets for averting disaster for much of our planet.

Since the construction and operation of buildings adds up to almost 40 percent of global carbon emissions (Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, and International Energy Agency), changing the way we build is a particularly impactful form of climate action. Few other human endeavors (i.e. transportation, energy production, and food systems) have as much potential to right our course in the climate crisis.

CARBON: WHERE DOES IT COME FROM, WHERE DOES IT GO?

Carbon is an element that exists in every living thing and naturally cycles between soil, plants, animals, oceans, and the atmosphere, and has done so for millions of years. It wasn’t until the 19th century that humans began extracting carbon-rich materials trapped in the earth’s crust (in the form of coal, petroleum, and natural gas) and burning them for energy for large scale industrial processes.

The natural carbon cycle became inundated and unbalanced as stores of fossil fuels were released from underground vaults and burned for energy, causing most of the excess carbon to accumulate in the atmosphere.

WHAT’S THE BIG DEAL?

The presence of carbon dioxide in the earth’s atmosphere increases its capacity to absorb and retain heat energy from the sun. Excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere contributes to a “greenhouse effect” which warms the planet, causing intensified weather patterns and rising sea levels that threaten human habitation throughout the world.

This is an oversimplification, for sure, as a warming planet has far more profound effects – severe prolonged drought, ocean acidification, and permafrost thaw to name a few. The industrial revolution that was powered by fossil fuels not only rapidly accelerated this carbon conundrum, but also paved the way for many other behaviors that degrade the natural environment.

Modern industrialized agriculture, for example, has depleted soils of vital nutrients, micro-organisms, and its great capacity to hold carbon. We have also turned vast forest areas into farmland which has released the carbon stored in those trees and eliminated their power to “vacuum” CO2 out of the air.

Fossil fuels have powered transportation systems that enabled suburban sprawl and the development of more forest land. It became easy to fathom turning wild habitats into human habitats with buildings, parking lots, and an extensive network of roads to connect them. Human actions have caused the extinction of so many animal and plant species that entire ecosystems are in decline. So called “development,” intended so support human life, is now threatening the viability of our species, as well.

AND WHAT ABOUT BUILDINGS?

The way we make buildings has played a huge role in this stress on the natural world. Through the sustainable building movement, we’ve come to focus on energy efficiency as the primary goal of “green building.” But what we’re really trying to do is stop emitting more carbon into the atmosphere.

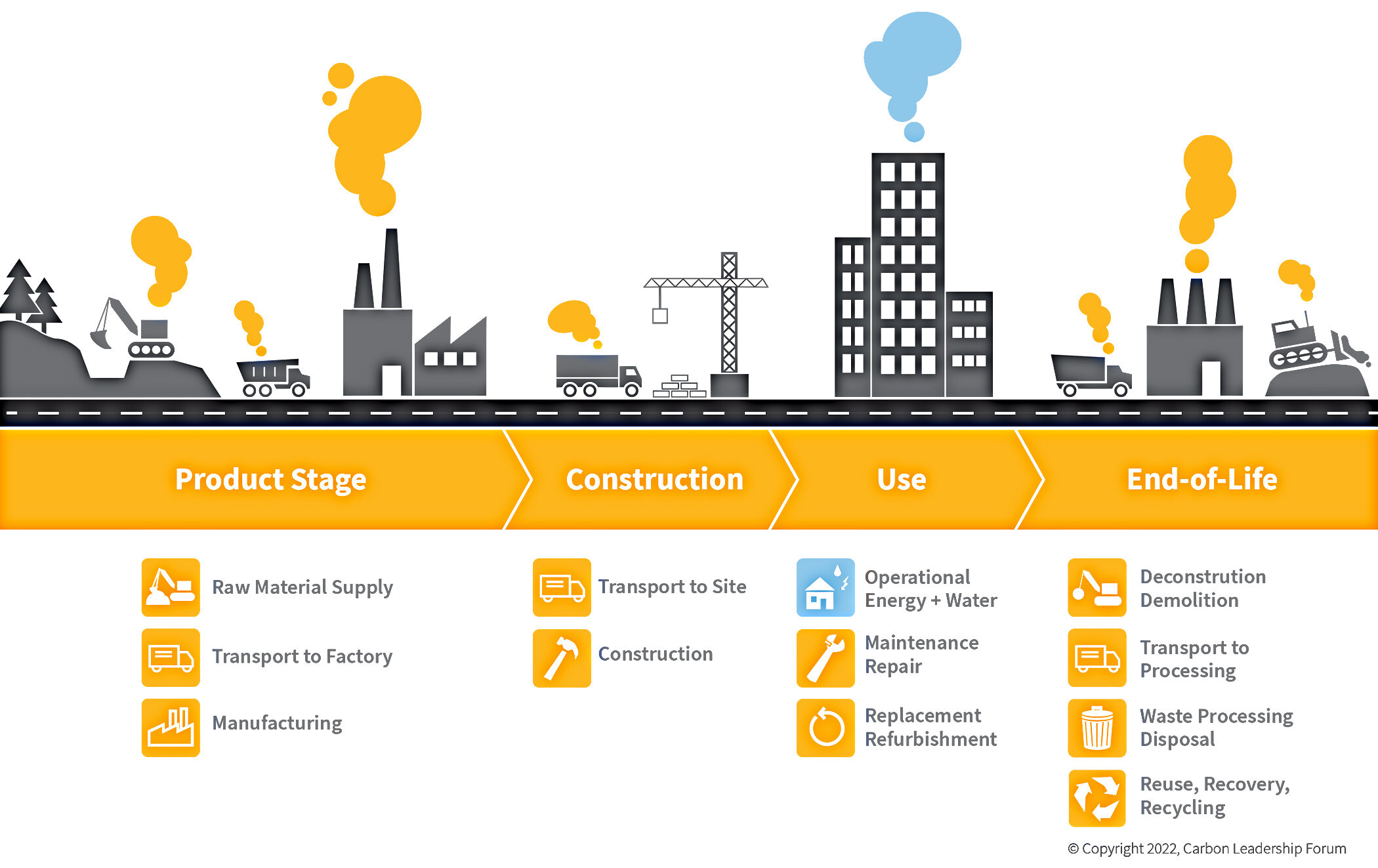

There are many ways a building contributes to carbon emissions. The operations of a building – lighting, heat, and air-conditioning – are the primary way. But what’s interesting is that a significant amount of the emissions come from the actual construction of the building and the many steps that lead up to it. Greenhouse gases associated with extracting raw materials, manufacturing them into construction materials, shipping them to the site, etc. account for about a quarter of a building’s carbon footprint (Architecture 2030).

Buildings are a necessity, and in designing them architects have an ethical obligation to protect human health, safety, and welfare. Building as we do now is fundamentally working against this charge.

How can we do better? How can we redirect a process that we have shaped to be destructive to the natural world into one that is regenerative?

WE KNOW WHAT WE NEED TO DO.

We have choices about how we build. The very crux of our work is a long sequence of design decisions that determine what a building will be. Every project involves the same sequence, and we are working to change it. A few basic principles have come to guide our process.

- Stop putting carbon into the atmosphere.

- Remove the carbon that is already up there.

- Repair the natural world.

- Re-train the markets to drive systemic change.

These parameters change the way we plan and design buildings in a range of ways. Specifying materials that aren’t made of toxic substances or petroleum-based chemicals is a great place to start. Indeed, using as many naturally renewable materials as possible cuts back on emissions and can contribute to healthy natural systems, which help absorb carbon. These things also mean better environments for humans. Finding better materials to build with remains a bit of a challenge in our current market. But change is coming, and we can help that along by working with manufacturers and encouraging them to change their ways.

BUILDINGS CAN BE

Buildings are many things – shelter, facility, sanctuary, home, art – but they can be so much more. Think of their potential to be water and air filterers, solar and wind energy harvesters, and even carbon capturers and storage vaults.

Forests are natural carbon sinks, and if properly cared for and harvested, could provide most of the material needed to make a building. The trees that go into buildings and don’t die and decay on the forest floor, also don’t let carbon escape into the atmosphere. Imagine, plant-based buildings! It’s already happening, enabling us to use less carbon-intensive materials like concrete and steel.

Perhaps buildings could evolve to draw carbon out of the atmosphere and inject it back into the ground. Landscapes around buildings can be thought of as green infrastructure, and act as carbon sinks as well as water retention and filtration elements. In this way, a collection of buildings – i.e. campuses, towns, cities – start to behave like natural ecosystems.

Buildings can also be part of a circular economy; we can adapt and reuse existing buildings or design new buildings to be deconstructed to repurpose components or materials. This approach to designing buildings not only makes them lighter on the planet but also healthy places for people. It points us toward a regenerative relationship with both the natural and built environments.

AND WHILE WE’RE AT IT: JUSTICE AND EQUITY

As we retool processes for planning and designing construction projects, we need to acknowledge the position of power and privilege we hold. Who has traditionally has gotten to sit at the drawing board, and who has not? Many communities are voiceless as they watch their places be shaped around them. Meanwhile those who do the shaping are predominantly white (over 69% of AIA architect members in 2020), male (74% of AIA architect members in 2020), and in socio-economic positions of advantage. A healthy built environment is one that acknowledges the role of equity and justice in the service of healthy, safety, and welfare.

Regeneration in the built environment means adopting new thinking about designing for the benefit of people and the natural environment. Communities must be empowered with the knowledge to take action toward positive, regenerative outcomes.

Construction projects are significant investments of resources; budget is a primary driver at every scale. Therefore the act of building, at any scale, is a great opportunity to both improve human welfare and take meaningful climate action. Every industry has a role and responsibility in this work. As architects we are in a position to both education and advocate; to grow knowledgeable clients and project teams. Clients that understand the full impact of their decisions are empowered to reduce their risk and create places where building occupants flourish. Ultimately, we can create beautiful, engaging places that tell the story of positive impact and reparation.