“Humans created the challenges facing this site, but it’s by turning back toward the natural world where we find inspiration.”

Planning for Resilience

April 25, 2023

Climate Change. Preservation. Culture. These words evoke complex ideas, connotations, definitions, and emotions. For Placework, they also define our work with and for Strawbery Banke Museum. Our most recent project addresses all three: a new Stormwater Plan.

As architects approaching historic preservation, we typically deal with buildings most directly. But preservation of whole places, including the natural landscape, can be just as important. The question at the heart of this work is often, what are we preserving? It’s rooted in communities and culture.

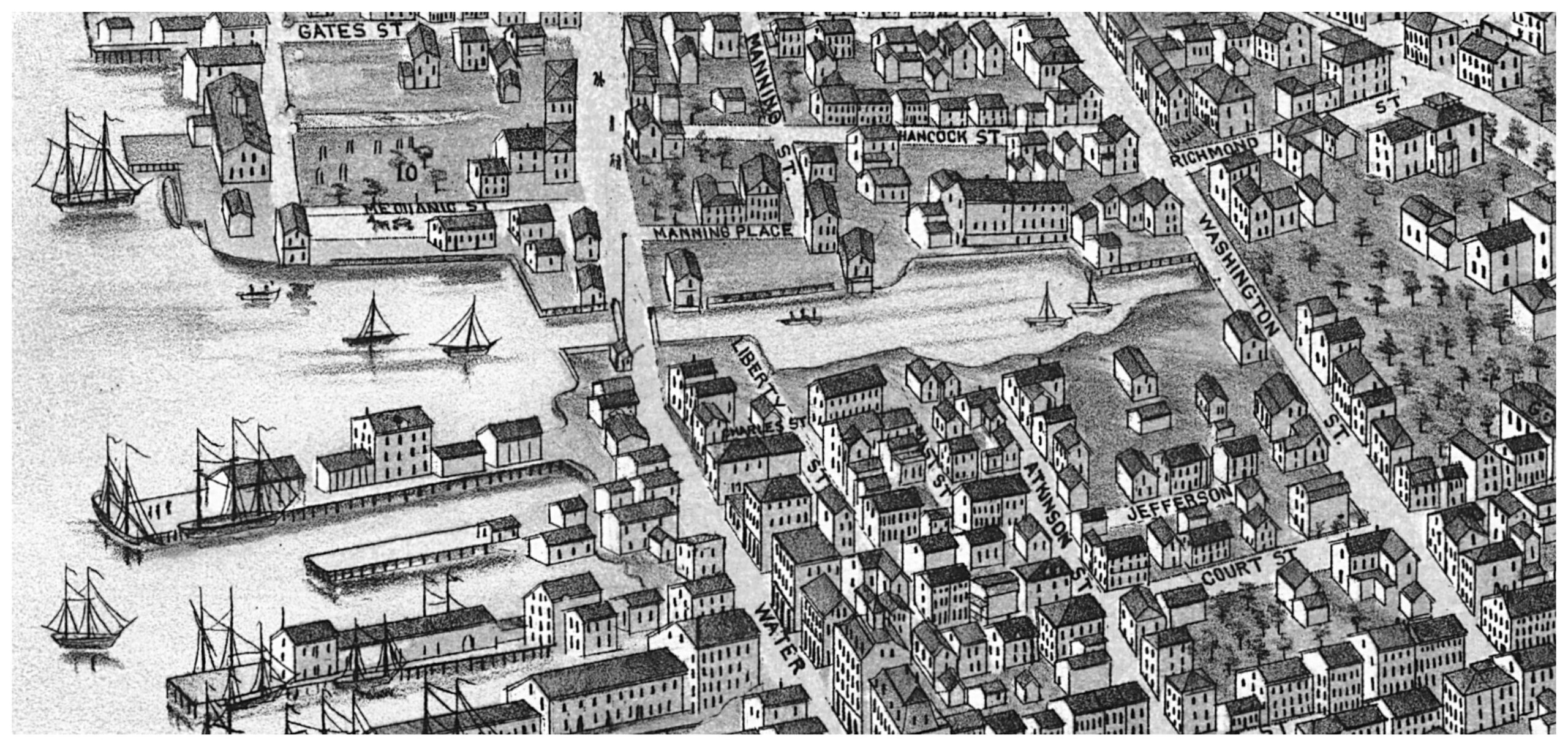

The mission of Strawbery Banke Museum is to promote understanding of the lives of individuals and the value of community through encounters with history. They do this while preserving a New England waterfront neighborhood in downtown Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

Strawbery Banke Museum is a cultural institution; its mission is not to merely preserve artifacts. They tell the history of the place by interpreting the items and buildings in their collection. Collaborating with the museum has been both instructive and influential for Placework Principal Brian Murphy. “I’ve learned that historic preservation is not simply about beautiful objects or important people but that this work is about sharing the stories of a place so the culture isn’t forgotten.”

The Threat

The land on which the museum sits is under threat. Strawbery Banke physically sits at about 10 feet above sea level, on the banks of the Piscataqua River. The museum campus is at the bottom of its local watershed. The rest of the developed town is at a higher elevation, so on its way to the river, water necessarily flows through the site. Water began to infringe on the museum’s ability to serve its mission when localized and large-scale flooding began to cause damage throughout the campus.

Water has gathered on the site since the area that was once the Puddle Dock inlet, now the central lawn of the museum campus, was infilled over one hundred years ago. Gradual changes in sea level and stronger storms due to climate change have accelerated and expanded the problem. The need for a survey of the situation and a long-term mitigation plan was very apparent to the museum staff.

“Humans created the challenges facing this site, but it’s by turning back toward the natural world where we find inspiration,” says Brian. “Over many generations, we have trained ourselves to think that we are separate from nature. But now is the time to have conversations, and do meaningful work around, addressing our climate crisis. This means we have to examine living in reciprocity with the natural world.”

Planning with a Team

At Placework, we recognized long ago that in order to design sustainably, we need to engage on a planning level. Buildings are grounded in a place and are part of a larger ecosystem. As planners, we must consider the distinct and diverse ecology of a landscape. And we also recognize that a project as rich and complex as this is best addressed by a collaborative team. We partnered with our colleagues at the Horsley Witten Group, a civil engineering and landscape architecture firm with a focus on environmental planning.

Multiple points of view and areas of expertise provide our clients with the perspective to plan for their needs. “Many factors are impacting this site: the built infrastructure, the stormwater drainage that the city has put in place, also the transportation infrastructure that obstructs the flow of water. Analyzing and exploring all of that is best achieved through collaboration,” says Brian.

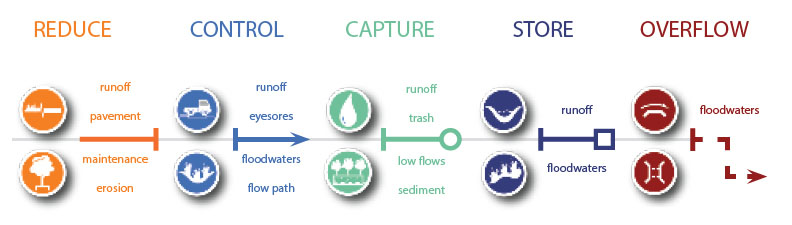

Some of that collaboration is with the land, and the earth itself. A core focus of the planning strategy became a constructed wetland in the middle of the site. “It’s now less about combating water or even managing water,” explains Brian. “It’s more like welcoming water because it belongs there, and it’s going to be there.” The team came together around the notion that the preservation of human-made artifacts is as important as the conservation of natural habitats.

Graphic Courtesy of Horsley Witten

Sharing it Out

Our work with Strawbery Banke Museum is ongoing, but it’s important to mark this milestone in their work as a resilient organization that educates the public. Part of that reflection process will take place at the upcoming Keeping History Above Water Conference hosted by the City of Portsmouth, Strawbery Banke Museum, and the University of New Hampshire’s Earth Sciences Center from May 7th to 9th, 2023. Brian will be joining his collaborators to lead a tour and share their experience with planning for stormwater.

Brian is also thinking about the opportunity to share his learning with others. “We are not the only community facing tough questions about preservation, culture, and climate change. Sharing our work with those already planning and designing for these conditions is work we will continue to do. This plan is only one answer to the ongoing question, how are we going to adapt and be resilient together?”

Resources

- Visit Strawbery Banke Museum, which opens for the season on May 1st, to explore the past, present, and future of a waterfront neighborhood.

- Attend the Keeping History Above Water Conference on May 7th – 9th, 2023.

- Watch this short video from our collaborators at Horsley Witten Group, about Green Stormwater Infrastructure.

- Read the full Stormwater Management Plan report